On February 11, 2000, the STS-99 Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission (SRTM) set out to remap the Earth in high-resolution radar to a precision never known before.

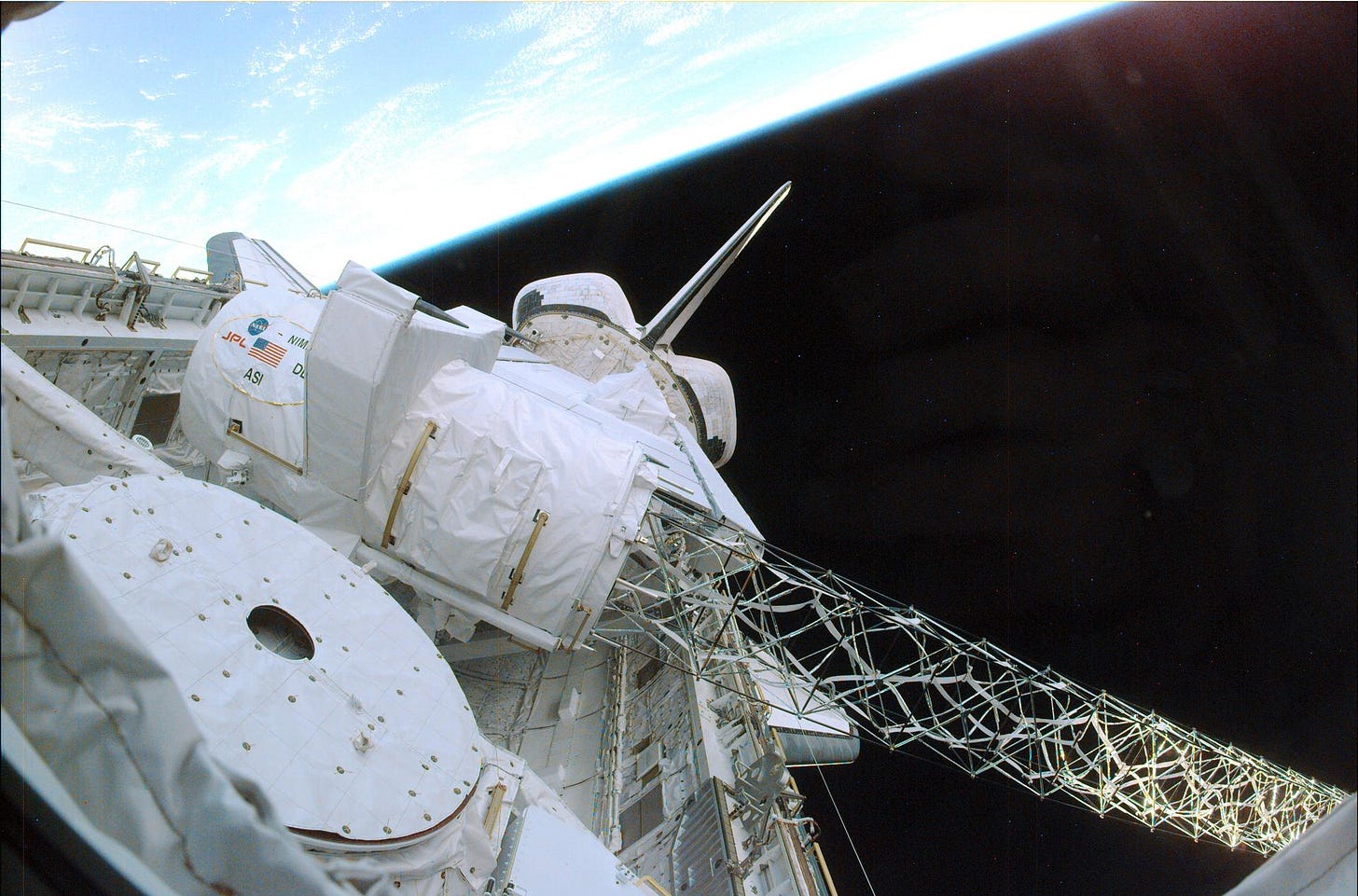

A 200-ft long mast jutted out into space from the Space Shuttle Endeavour that beamed radar down to Earth and recorded the reflections that came back. The SRTM radar was able to obtain 3-D topographic images of the world’s surface up to the Arctic and Antarctic Circles. It took 5 years to create the map from the terabytes of data.

My sister was the payload commander on that mission. My family participated in supporting her from Earth. I may have mentioned that I come from a family of engineers. Unlike writers, who deal in the abstractions of language, engineers like to play with things in the real world—like my brother-in-law, Rob Fransham, making their front door into a 9 and three-fourths red brick railroad station for a Harry Potter themed Halloween party.

So it’s not that strange that the idea of initialing the SRTM dataset from the STS-99 mission my sister Astronaut Janice Voss was flying seemed like a fun project to the Franshams.

It started out as a conversation between Rob and a NASA engineer who was involved with the SRTM mapping about how they calibrated the data. He said they looked for known places that could be spotted in the data and use the known elevation and location of that spot to map onto the data. So, if you had a building or some kind of facility, a hot spot, that cleanly reflected the radar and you knew its height and location, it could provide a marker for the data that’s relayed to the shuttle and captured on the SRTM dataset. Naturally Rob asked if it was possible to create a hot spot, that is, make a reflector bright enough to “send a message” to space. The elements of the calculation included the distance between reflectors on the ground, the concentration of points needed to show up as something more significant than noise, and how to maximize the reflectivity. “Yeah, all you have to do is set up a radar reflector in a series of dots in an area 60 meters apart to have a large enough area to be visible from space.”

The conversation evolved into the specifications for how one might create a reflection back into the stream of the SRTM data that would represent Janice’s initials, JV (which were also sometimes used as a nickname for her by some of the folks she worked with on the mission). Rob bought 4-ft by 8-ft radiant acoustic insulation sheets, the kind that make a barrier you use in your attic to reflect the heat away from your house. The material is a foam core board with a metallic surface on one side. The team cut the sheets in half to 4 by 4-ft, then cut each diagonally in half into two triangles. The triangles were glued and taped together at 90-degree angles to each other to form a 4-ft tall corner (with the shiny insulation inside the corner) and then attached to a base (with the insulation up) so it formed the corner of a box. This construction mimics that of the retroreflector, which is commonly used for visibility, for example, on bicycles. The corner configuration with three mutually perpendicular sides means that no matter which surface the incoming beam hits, it bounces of the sides so that eventually it reflects back almost exactly parallel to the path of the incoming beam, returning the signal to the source.

The board had to be tilted at a 10 or 15-degree angle, the best angle to reflect back to the boom stretched from the sides of the space shuttle as it passed overhead. Soda cans propped up the reflectors at the right angle. Bricks in the middle of the part of the letter held the board in place, so it wouldn’t blow away. The 15-degree angle correlated with the height of a soda can, and a brick on top kept the reflector triangles from blowing over in the wind. The total space that was needed, they calculated, would be larger than a football field. The reflections had to be away from other objects that were reflective to stand out. One of the rare open, undeveloped spaces in the Houston-Clear Lake area with a large enough area was at Ellington Air Force Base. Not too distant from its own cow pasture history, Ellington had just bought another parcel of pasture for expansion. The land was not controlled by private interests and undeveloped and the base was sufficiently used to hosting astronauts that it might be sympathetic to a personal astronaut project.

It took more than one trip to Ellington for Vicky to get permission for the project. She had to assure the base commander that the reflectors would be harmless to the operation of flights at Ellington and not interfere with the radar they used for landing. They wouldn’t be generating a radar signal, just reflecting back the shuttle radar.

The project would have to be accomplished during the three passes over Houston during three consecutive days. The reflectors had to be in place at the exact time the shuttle would pass overhead, but they couldn’t be left there before or after.

Vicky was lead on implementing the project. They picked the flattest part of the field with Johnson Space Center’s Neutral Buoyancy Lab in the distance. With the flat space, and no readily available markers, placing each reflector at a distance from each other was a challenge.

The first window of opportunity, the afternoon of the first shuttle pass over Houston, it took Vicky so long to carry the bricks, cans, and reflectors underneath the pasture fence, across the field of unmowed grass, and into place that only some of the points on the V got placed. The remnant cow pies were dry, but still easy to stumble over. Vicky called in some help from moms who were at home during the day for the second pass, also during daylight. The piles of bricks to hold the reflectors to make up the letters of Janice’s initials were left, but the grass was so long they couldn’t be seen until you were on top of them. The second day the lady who gave permission from Ellington came down to check on the project, and NASA employees who worked in the adjacent buildings stopped by to ask, “What are you guys doing over there?” The team looked like ants from the NASA buildings placing these piles of bricks in the field. Rob emailed Janice on the shuttle that day (Wednesday, Feb. 16), “We were partially successful with our "greeting card" this morning. We'll try again for your Thursday overpasses.”

The final attempt occurred on a pitch-black night with no moon, no stars, and a wind. Vicky collected the girls (my two nieces, Kimberly and Amanda, 9 and 12, respectively) and some of their neighborhood friends to get the reflectors set up in place in time. The night was so dark, the parents could only see the girls by crouching down to see their silhouettes against the background lights at Ellington. And the wind was such you could only be heard in one direction. You could send the girls out, but you couldn’t call them back.

Busy getting the reflectors set up in time, they hit a snag when they angled too far for the leg of the V, venturing into a marker for the J. The miscalculation caused them to be unable to locate the J markers. They were running out of time, and they couldn’t see in the dark. It looked like they might have to give up on the project until Vicky realized the mistake and was able to correct course. They were able to quickly locate the markers and get the J reflectors in place in about 20 minutes. It was a close call, though. They were holding the last reflector up by hand at the last minute for the shuttle pass-over. They couldn’t see the reflectors once they were set up, and the wind might have altered the alignment slightly, but they made it! Rob was able to email Janice Feb. 18, “Our final attempt last night (MET [Mission Elapsed Time] 6d/8h/4m/52s) to build the sign should have been successful. We couldn't see you even though the sky was clear, but we waved anyway.”

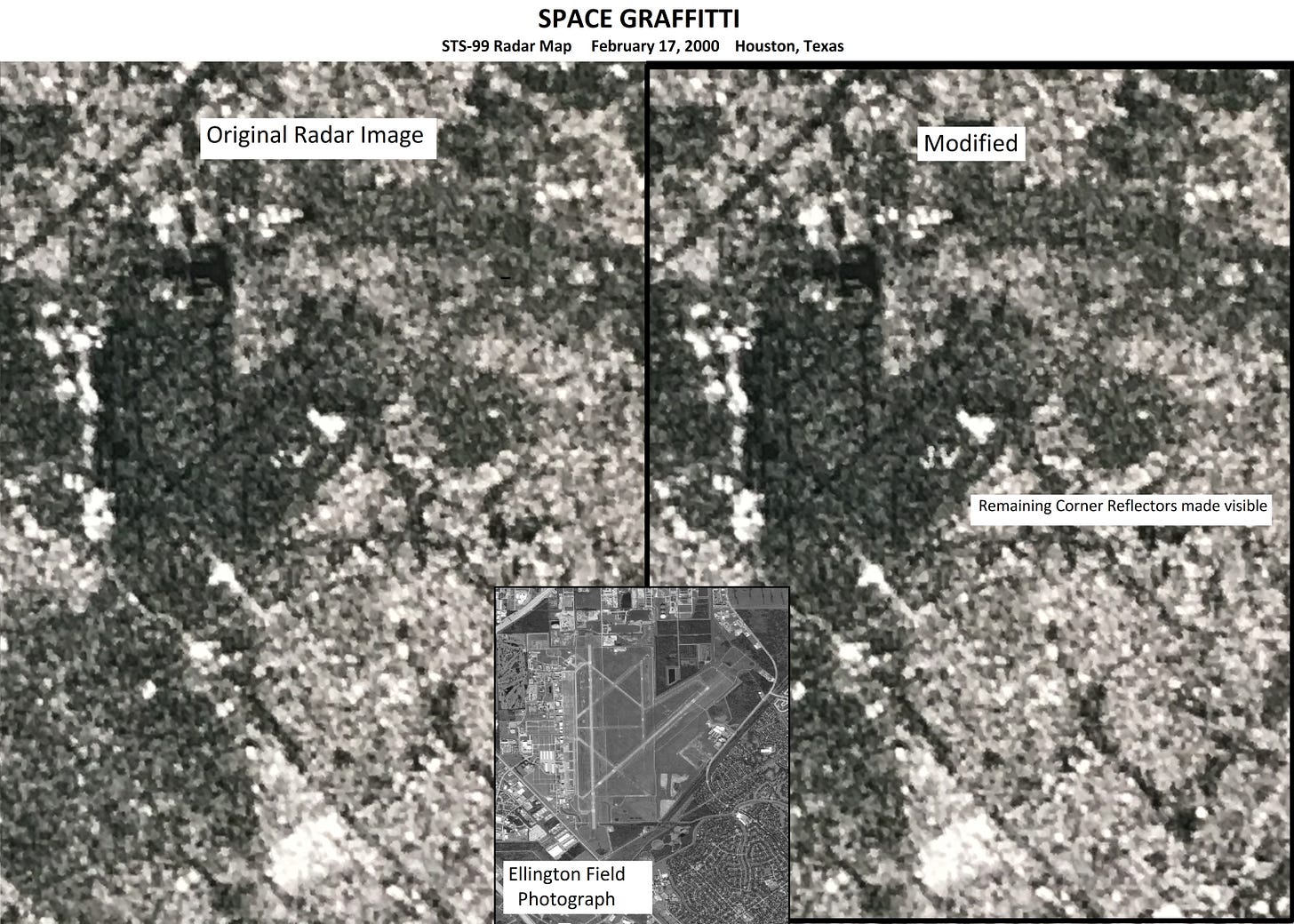

In the mission debrief for friends and family after the astronauts returned, Rob got called out. “Now, we are looking for a member of the Voss family that was doing graffiti in space. So, if anybody knows who this character is that causes space graffiti that shows up on our map, make sure you turn them in because we can’t have this going on.” The initials were near a known hot spot, but you had to know they were there to find them. Janice had given the engineers a heads up to watch for them when they were doing their calibration work.

The Franshams were rewarded with a picture capturing the initials. “It was really fun,” Vicky said. It was completely homemade with the girls involved, and “the really exciting part was all the work actually sent the message to space that got captured in the data.” Good science and math project, but also, immortalizing our sister, NASA Astronaut Janice Voss, STS-99 payload commander, in the dataset that changed the world.

What a wonderful family story, Linda! I love that it combined Physics & Graffiti to create a nod to Janice for her role in the mapping project! In a similar but much smaller way, today's electrical engineers sometimes sign their work with microscopic signatures, initials, or other "easter eggs" in the circuit boards and microchips that they design.

I was wondering if your sister's family actually used 3-D corner reflectors rather than flat sheets of insulating board, as corner reflectors are quite forgiving with angular placement, and would give a much higher signal-to-noise ratio, even if they are misaligned significantly.

My question was partially answered by the label in the right hand modified image, "Remaining Corner Reflectors made visible." Ideally-constructed corner reflectors send reflections back to their destination quite accurately, so it makes perfect sense that Rob used that design. It would have been my first choice!